The island of Iceland was formed as a result of volcanic activity — it lies on the divergent boundary between the Eurasian plate and the North American plate, over which one can walk across via a bridge at Miðlína — so the existence of lava tubes is of no surprise…

Exploring the Inside of a Dormant Lava Tunnel in Iceland

…and visitors can walk through an actual dormant lava tube — through which hot molten lava once flowed thousands of years ago — at the Raufarhólshellir Lava Tunnel.

I entered the facility through a door from the gravel parking lot…

…and once I paid for the tour, I was given a helmet which has a light on it. I wore sneakers and had no problem with them; but good hiking shoes or boots are recommended. Because the temperature inside the cave hovers between 0 and 4 degrees Celsius — which is between 32 and 38 degrees Fahrenheit — and water sometimes drips from the ceiling of the cave, wearing a waterproof jacket is recommended.

Visitors cannot go into the lava tunnel by themselves. A guide leads the tour at all times…

…starting with walking from the office to the entrance of the lava tunnel.

After descending the stone stairs, visitors are immediately treated to various colors on the rocks inside of the lava tube.

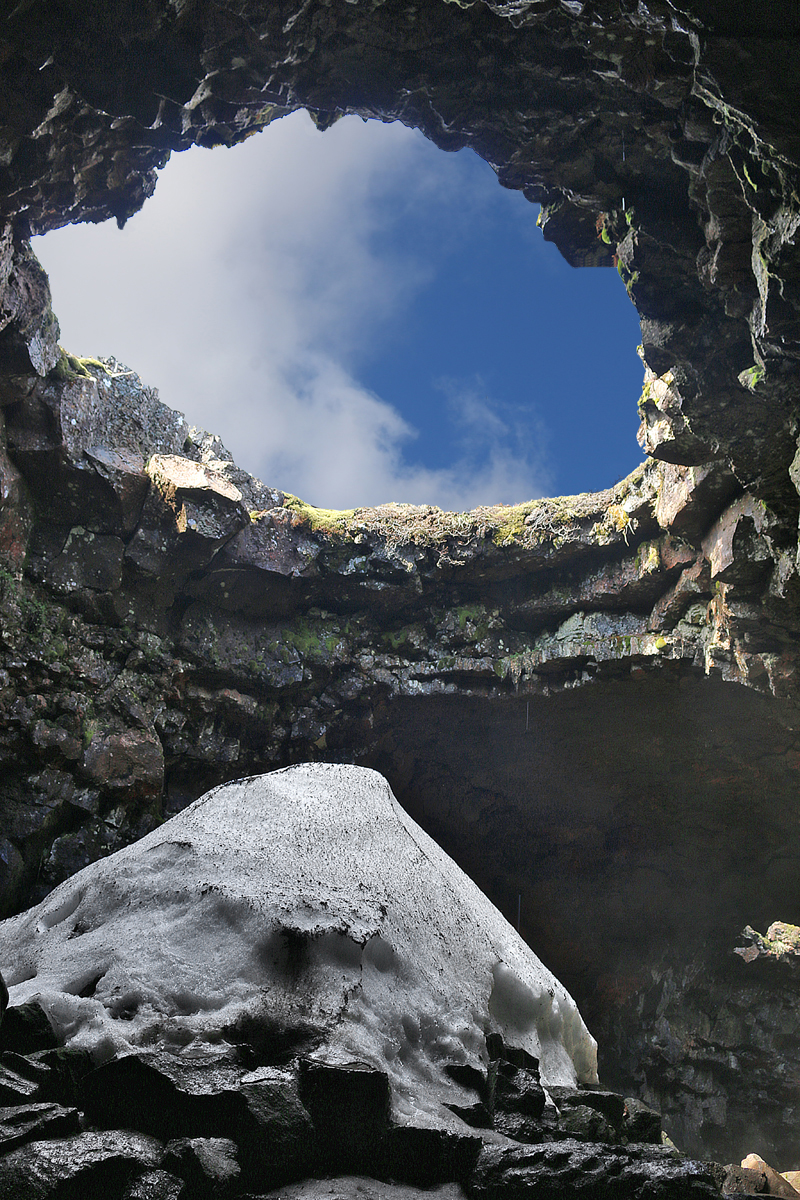

A pile of old snow remains under the blue skies through an open hole in the dormant lava tunnel.

What immediately stood out for me was the aforementioned palette of colors — some of them rather vibrant — of the rocks and walls inside of what is considered to be the fourth longest lava tube in Iceland. Every color seemed to be represented.

The colorful walls are what remain of the inner workings of a volcanic eruption while walking in the path of lava which once flowed during the Leitahraun eruption.

The Leitahraun eruption occurred east of the Bláfjöll mountains in Iceland approximately 5,200 years ago.

You need to be in good physical shape to be able to walk through rough terrain with big boulders without difficulty inside the dormant lava tunnel…

…as well as being able to balance yourself well — especially in areas where the rocks are slippery and wet.

The total length of the tunnel is approximately 4,500 feet or 1,360 meters — 3,000 feet or 900 meters of which comprise the main tunnel.

Several piles of old snow are found under other open holes in the lava tunnel…

…and steam rises from them due to the warmer weather from the sun.

The dripping water from above left a couple of droplets of water forming on the lens of my camera, which resulted in the cool effect in the photograph shown above.

The ceiling has caved in near the entrance of the tunnel, creating three columns of light through the aforementioned holes inside the lava tube…

…and the three large piles of snow are located directly under the spots where the ceiling had caved in.

Because the interior of the lava tube stays cool all year round, I would not be the least bit surprised if more snow accumulated before the existing piles had a chance to completely melt.

Spectacular ice sculptures are formed inside the entrance of the cave every winter, which results in the experience of visiting the lava tunnel even more breathtaking.

The elevated walking paths and viewing decks were installed inside of the dormant lava tunnel during the first half of 2017 in such a way that they can be easily removed and will not leave any permanent damage to the natural beauty inside…

…and electrical lighting was added along with the improvements as well.

Prior to the improvements, no admission was charged to anyone who wanted to freely enter the dormant lava tube…

…but due to the darkness inside and the collapse of parts of the ceiling, it was difficult and dangerous for visitors to navigate through it — to the point where some visitors had to be rescued at significant cost.

A collection of ice stalagmites which were illuminated by electrical lighting created a scene of fragile beauty.

The armies of ice stalagmites appeared to stand at attention every time a visitor passed by.

Piles of toilet paper were among the several metric tons of trash, refuse and waste which were removed from the cave during construction in the first half of 2017.

Lava tubes are a natural conduit which are formed when an active lava flow of low viscosity eventually develops a hard continuous crust, which then thickens and forms a roof above the lava stream which is still actively flowing.

Raufarhólshellir was full of stalactites up until the last century; but starting in the 1950s, the number of people who visited the tunnel steadily increased — and the stalactites began to disappear as a result.

Almost all of the stalactites — many of them in the form of lava straws — are gone from inside of the lava tube.

Despite the illumination of the lava tube itself, the lights on the helmets were consistently useful for enjoying the experience.

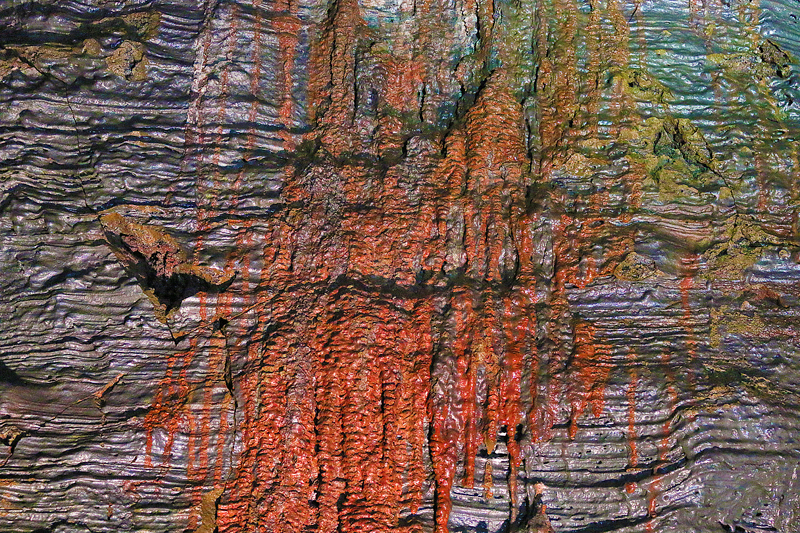

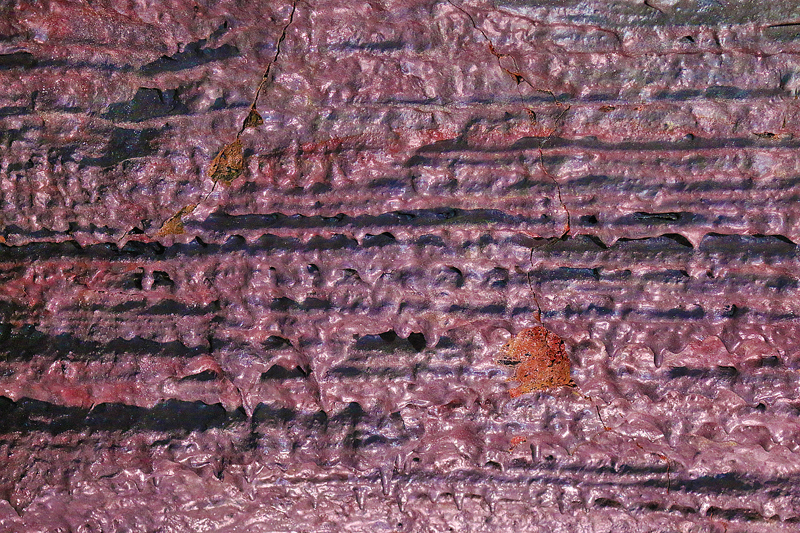

In parts of the walls of Raufarhólshellir, some of the hardened lava seemed to emulate dripping wax from candles.

The substance did not feel like wax, though — rather, just smooth, hard and glossy rock.

The molten lava was so hot that it apparently carved patterns into the wall.

This is a closer view of what the molten lava had left behind.

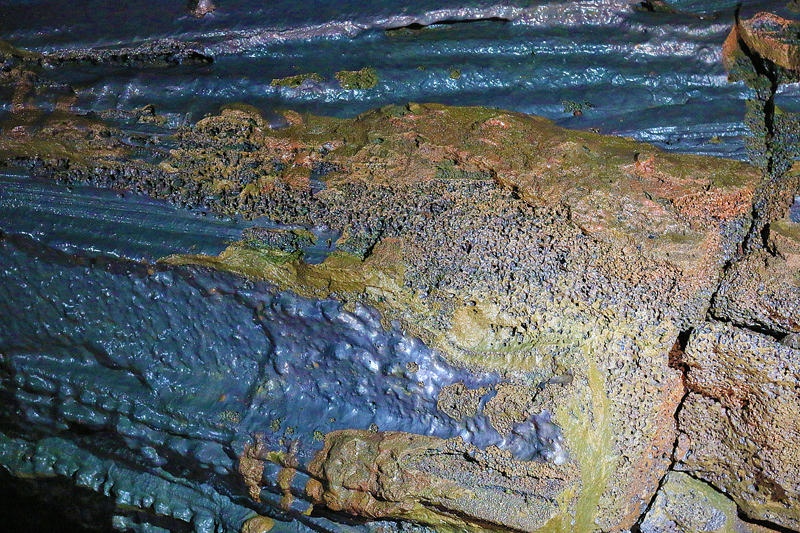

This part of the wall seems like it is soft, thick and gooey…

…but it is indeed hard, as evidenced by this massive straight crack in the wall of the rock.

The color of the lava has changed over time — in this case, a deep blue and pale yellow with some splashes of pale orange.

I was fascinated by the differences in textures along the walls, ceiling and floor of the lava tube.

This photograph shows a closer view of the ceiling at one point in the lava tube, with its various red and tan hues — part of it with a smooth surface…

…while this part of the ceiling just a few meters away had a rough and rocky surface, with hues of deep dark red.

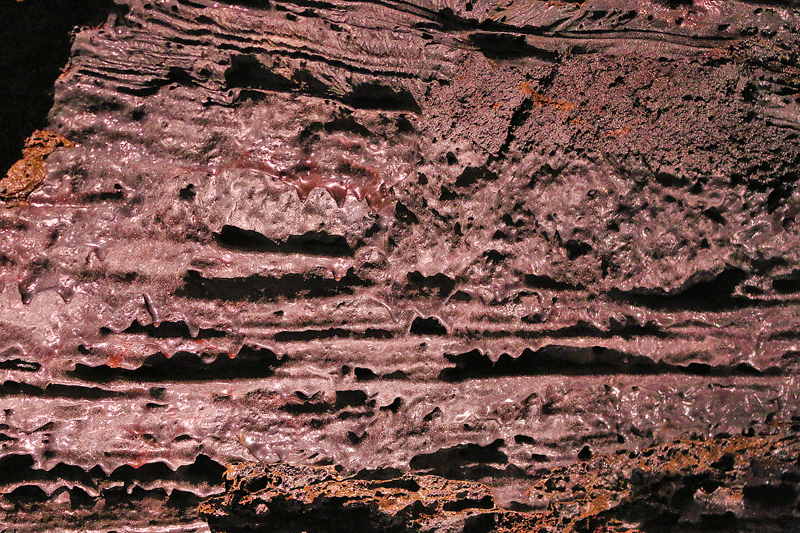

This portion of the wall had a rich chocolate color — matched by a texture that further emulated that illusion.

The layers of lava along the walls seem to tell a story of what happened thousands of years ago.

One can see — perhaps almost feel — the immense weight of the massive amount of rock in the photograph shown above.

To give an idea of scale, the staircase is shown on the left — and notice how far it goes up in the background…

…so you can only imagine how vast is this portion of the dormant lava tunnel from floor to ceiling, which is only accentuated by the changes in texture.

At one point, the guide instructed us to turn off the lights on our helmets; and then all of the lights inside of the section of the lava tube we were in were turned off as well. We all sat in silence in pitch black for a few minutes — similar to the experience which I had at Mammoth Caves National Park back in 2014.

At the end of Raufarhólshellir, the tunnel branches into three smaller tunnels where magnificent lava falls and formations are clearly visible.

The textures and colors of the lava tunnel change every few meters, as the texture of this wall seems to resemble the skin of a reptile.

Fine cracks have formed in this wall over the years and will only grow larger and deeper, as evidenced by the small piece which has already dislodged and fallen, leaving a noticeable blemish on the wall.

Although Raufarhólshellir can be referred to as a cave, one major difference between a cave and a lava tunnel is that a cave is formed by the dissolution of limestone by rainwater — which picks up carbon dioxide from the air and transforms into a weak acid as it percolates through the soil and eventually slowly dissolves out the limestone — rather than by the flow of lava from an active volcano.

Another massive crack illustrates the stress of the wall of Raufarhólshellir from the weight of the rock and the natural forces of nature.

The vibrant red and bluish-purple hues of the lava — which resemble part of the color scheme of Southwest Airlines — create a vivid contrast…

…while the interesting formations and shapes of the warm gray and brown lava are forever frozen in time, showing what the molten rock was like when it was still flowing and dripping.

I found this rough surface to be cool — almost as if it can be found on the moon.

Meanwhile, this part of the rock wall is not all that it is cracked up to be — pardon the poor grammar.

On our return, we once again passed by the ice stalagmites.

Each formation represented a work of art — almost as though each piece was a sculpture.

Some of the ice formed stalactites from the lower ceilings…

…while others formed as stalagmites which resembled miniature cities with tall buildings.

Each ice formation was a work of art; and together, they combined yet another overall work of art.

I thought that the ice formations were — well — pretty cool.

The width of the lava tunnel can be as much as 30 meters wide, with headroom up to ten meters high — but other parts can be narrow with a low ceiling.

Passing by the mounds of snow and ice sculptures again, it was time for this group of visitors to leave the dormant lava tunnel.

Summary

The Raufarhólshellir Lava Tunnel is open every day from 9:00 in the morning through 5:00 in the afternoon. It is located approximately 41 kilometers — or almost 25.5 miles — from Reykjavik; and the drive should take 34 minutes in the usual traffic.

The standard lava tunnel tour costs 6,900 Icelandic krona per person, which is currently slightly greater than $55.00 United States dollars. This tour allows you to explore the tunnel in an easy and enjoyable manner within the duration of one hour. A foot bridge was built for easier access; and lighting in this part of the tunnel highlights the changing colors and clearly shows the powerful volcanic activity that formed the tunnel.

Other tours are available at various costs and durations.

Ample free parking is available.

During the busy summer tourist season, you may want to book your tour at Raufarhólshellir Lava Tunnel in advance to reserve the hour at which you want to visit, as they tend to sell out. When I arrived at the facility, I could not join the tour that was scheduled because it was sold out; so I had to wait an hour for the next one.

I highly recommend a visit to the Raufarhólshellir Lava Tunnel — especially if you enjoy nature and geology.

All photographs ©2018 by Brian Cohen.