Note: This article pertaining to I Met the King. His Name is Tut Ankh Amun. was originally published on Sunday, July 21, 2019 at 6:42 in the evening and has been updated.

In celebration of the tomb of Tut Ankh Amun in Egypt once again being open to visitors after undergoing extensive and painstaking restoration for almost a decade, I thought I would impart the experience of my visit from the spring of 2015 — but because I was not allowed to bring my camera within the Valley of the Kings, I unfortunately have no photographs to show you of my visit.

I Met the King. His Name is Tut Ankh Amun.

No bridge exists directly between the city of Luxor and the Valley of the Kings, which is located on the other side of the Nile River. I had to drive approximately 17 kilometers south to the Luxor Bridge — which is the nearest bridge to Luxor and is a half hour drive south of Luxor — and cross the river before driving another 19 kilometers north to see the famous pharaoh who is popularly known as King Tut.

In other words, I had to drive 37 kilometers over the duration of one hour to get to what I was able to see across the Nile River in what seemed to be one giant U-turn — but I digress.

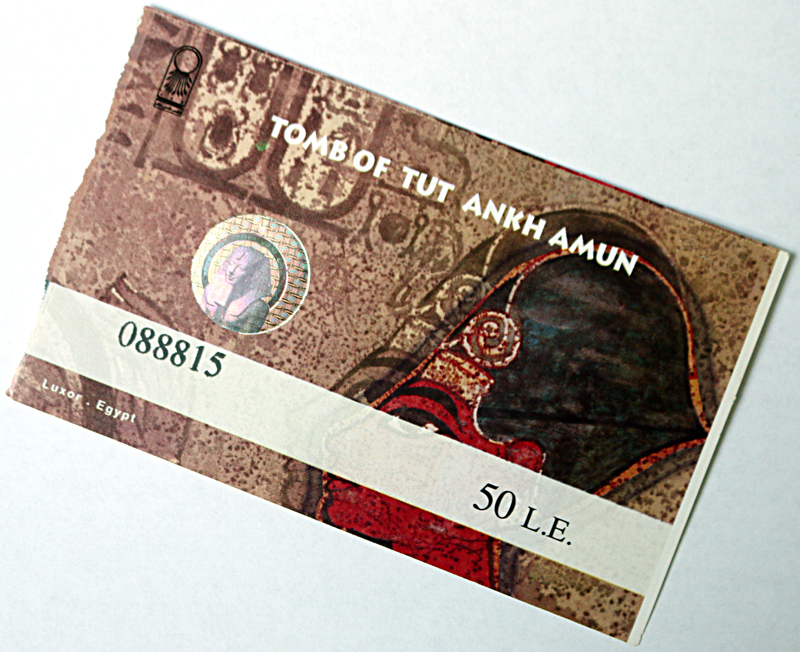

After parking the car — when I purchased the tickets to enter the Valley of the Kings — I managed to somehow secure a discount, as the cost to enter the tomb of Tut Ankh Amun was in addition to the cost of general admission into the Valley of the Kings. The man inside the shack at the entrance — who had some of the ugliest and nastiest teeth I had ever seen, with equally dark yellow nails attached to his long bony fingers — retained half of that discount as a sort of kickback. I wound up paying 50 Egyptian pounds — which at that time was the equivalent of almost $7.50 — as shown on the ticket in the photograph at the top of this article.

He also informed me that no photographs were allowed to be taken; and that I was required to check my camera before entering the Valley of the Kings. Alerts suddenly went off in my head not to check my camera. Inconspicuously as possible, I reluctantly returned to the car to hide my camera in the trunk, figuring that was the lesser of two evils.

Perhaps other visitors were successful in photographing the mummified body of Tut Ankh Amun. On that day, I sadly was not one of them.

I returned to the entrance of the Valley of the Kings to receive a map to the different tombs and places. Unsurprisingly, I was immediately approached by a tout outside of the specific tomb of Tut Ankh Amun and told him that I was not giving him anything. “Oh you can take pictures,” he said. “Go in and look at King Tut’s body.”

Upon descending into the tomb through a narrow tunnel which led me to a viewing platform, I noticed that video cameras were placed around the inside of the tomb itself; and I surmised that this was a way to entrap visitors into paying a fee or a fine of some kind after getting caught. The tout did impart a lot of history about the tombs and sarcophagi in the Valley of the Kings, though.

The tomb was discovered almost intact in 1922; and it was also considerably cooler than the ambient air outside — thankfully, I must admit.

The middle section of the mummified body of Tut Ankh Amun — who was by himself inside of the tomb — was covered with cloth. I was told that he used to be in a sarcophagus; but opening and closing it supposedly crushed his middle section. I could actually see the little holes in the gauze…

…and what seemed to be an optical illusion, when I looked at his feet from the front, he had five toes on one foot; but when viewed from the back, that same foot looked like it had six toes.

Tut Ankh Amun was either a short person, or his mummified body had shrunk over the years; but he was buried in three different sarcophagi: the outermost one was of wood; the middle one was of wood overlaid with gold foil; and the innermost one was entirely of gold. A lot of steps are involved in mummification, as it is not a simple process to go through — and that it lasted all these years simply amazed me.

The paintings — I do not think they are actually hieroglyphics — on the walls in the tomb were not the most impressive. Then again, I believe I viewed them before they were completely restored.

In some ways, the tomb of Merneptah — which I also visited — was actually more impressive. I intend to impart my experience — of which I also have no photographs — in a future article.

Although the tomb of Tut Ankh Amun is worth a visit all by itself, I had to visit the Egyptian Museum in Cairo to see the treasures with which he was buried.

When I visited in 2015, admission to the Valley of the Kings was 160 Egyptian pounds — or slightly less than ten United States dollars — and admission for children is a discount of 50 percent. The extra cost to visit the tomb of Tut Ankh Amun has increased to 250 Egyptian pounds; but the currency has severely devalued since I visited in 2015 to the point where one Egyptian pound is worth roughly six cents — so expect the visit to cost slightly greater than $15.00.

Final Boarding Call

When I visited in 2015, admission to the Valley of the Kings was 160 Egyptian pounds — or slightly less than ten United States dollars — and admission for children was a discount of 50 percent. The extra cost to visit the tomb of Tut Ankh Amun had increased to 250 Egyptian pounds. 9:00 in the morning was when it opened to visitors. The structure of the admission fee seems to have changed over the past ten years.

Situated on the ancient site of Thebes on the West Bank of Luxor, the Valley of Kings is the ancient burial ground of many of the New Kingdom rulers of Egypt. At one time, a ticket allowed visiting three of the 63 tombs on site — including the tomb of Ramses IV, among others — except the tomb of Tut Ankh Amun, which required an additional ticket.

No photographs of the tomb are included in this article because at the time I visited in 2015, photography was technically not allowed. That rule was strictly enforced unless a bribe was paid. I understand that visitors to the tomb are now permitted to freely photograph the inside of the tomb as long as a flash is not used; and cameras are supposedly no longer surrendered at the area where tickets are purchased…

…so unless I return to the tomb, I will alas never have a photograph of myself with my friend Tut Ankh Amun. Ah, I will always remember the great times we had while we were together…

You can visit the tomb as long as you like during the hours in which it is open, which is currently from 6:00 in the morning through 5:00 in the afternoon.

The tomb of Tut Ankh Amun is located in the Valley of the Kings near the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut across the Nile River from Luxor in Egypt.

Admission fees

- Foreigners:

- Adult: 700 Egyptian pounds or approximately $14.16 in United States dollars

- Student: 350 Egyptian pounds or approximately $7.08 in United States dollars

- Egyptians and Arabs:

- Adult: 40 Egyptian pounds or approximately $0.81 in United States dollars

- Student: 20 Egyptian pounds or approximately $0.40 in United States dollars

If you are interested in visiting Egypt, the following list is a series of articles pertaining to my experiences in that country:

- 6 Reasons Why You Should Visit Egypt Now

- Great Sphinx of Giza in Egypt: A Photographic Essay

- Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut in Egypt: Part One of A Photographic Essay

- Trapped in the Toilet of My Hotel Room in Egypt

- Arguably the Best Service I Ever Received From a Hotel

- As I am Lounging on a Hammock Along the Shore of the Nile River…

- I Became Guest of the Day at This Hotel Simply Because I Drove a Car

- 8 Tips on How to Drive in Cairo and Other Parts of Egypt

- I Drove on One of the 10 Roads You Would Never Want to Drive On and Did Not Even Realize It

- Renting a Car in Egypt: My Experience

- 9 Tips on How to Deal With Aggressive Touts When Visiting Egypt

- The Chaos Known as Cairo International Airport

- 11 Travel Photographs You Should Stop Taking Right Now?

- Should Attractions in the United States Charge Different Fees for Non-Residents?

- Russian Airplane Crash: Should You Travel to Egypt? Is it Safe?

All photographs ©2015 by Brian Cohen.