The reasons why New York wins with congestion pricing — regardless of the outcome — are quite simple, as I confirmed during my recent trip to the city earlier this month.

Why New York Wins With Congestion Pricing — Regardless of the Outcome

“Preliminary data shows that traffic was down 7.51 percent last week, compared to the same time last year and approximately 219,000 fewer vehicles entered the Central Business District in the first week the program launched”, according to this official press release from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority of New York that was published on Monday, January 13, 2025 — eight days after the congestion pricing plan went into effect. “Drivers saw faster and more reliable trip times, and many express bus riders benefitted from shorter commutes.”

The tolls that are collected from motor vehicles that enter the designated congestion zone are expected to raise as much as $800 million per year. The vast majority of the funds will go towards public transportation — such as the subway lines.

I walked south on Seventh Avenue from West 48 Street north of Times Square to Christopher Street in Greenwich Village to see for myself; and the results were mixed: sometimes no moving motor vehicles were spotted on major avenues for several blocks; and sometimes congestion was as bad — or worse — than prior to the implementation of the congestion pricing plan in the central business district of Manhattan.

I must note that many of the major avenues have fewer lanes available to motor vehicle traffic over the years due to the implementation of pedestrian plazas and lanes for bicycles and buses — and that does not include construction zones and delivery vehicles blocking traffic, which are also significant impediments.

As one example, the photograph shown above was taken on Seventh Avenue facing north from West 38 Street towards Times Square on a Wednesday afternoon during the week. One lane is dedicated to bicycles; while another lane is simply blocked off with large blue blocks and plants in heavy pots. Regardless of whether this was an improvement, only three lanes can be used on Seventh Avenue — so of course the avenue became more congested; and traffic was still congested along Seventh Avenue despite the implementation of congestion zone toll pricing.

On the other hand, traffic on Seventh Avenue South at West 4 Street and Christopher Street on that same Wednesday afternoon seemed to be lighter than normal…

…as was traffic at the approach from the Lincoln Tunnel at West 30 Street between Ninth Avenue and Tenth Avenue. Note the two sets of gantries that were erected overhead to read the license plates of motor vehicles that pass under them to collect the toll electronically.

My observations were obviously not scientific nor conclusive during my extensive walk around the lower half of Manhattan, as I saw example after example of where the congestion pricing seemed to alleviate traffic — and where it did not seem to help at all. Too many factors ascertain what the ultimate traffic pattern will be like on any given day at any given time in any given place; so I would conclude that the results were mixed at best…

…and the results might have been completely different on the next day…and the next day after that…

Possible Loopholes

At many areas along West Street — such as at this intersection with Eleventh Avenue — I noticed signs that announce the beginning of the toll zone for the congestion area — but no gantries were in sight.

I found an officer of the traffic department as he was writing out tickets to illegally parked vehicles, which could result in them getting “booted”. I repeatedly asked him about how the toll is collected when gantries are not in sight when people drive in from West Street, which is outside of the toll zone. He kept answering me in an almost unrecognizable and barely understandable broken accent that the toll zone begins at 60 Street. I guess he never understood my question.

I eventually realized that many of the gantries were not erected at the actual edge of the toll zone, as some of them are several blocks in. Does that mean that drivers can successfully evade tolls in certain areas within the toll zone?

A man asked me if I knew where the violinist was at an event that I attended that was sponsored by Hilton. I told him that I knew nothing about the violinist; but then the topic of our impromptu conversation eventually focused on the congestion zone. He did not tell me details; but he claimed to have figured out some ways to legally bypass the gantries and not pay the toll within the congestion zone.

I could not verify the veracity of his claim.

Response From One Ride Sharing Service

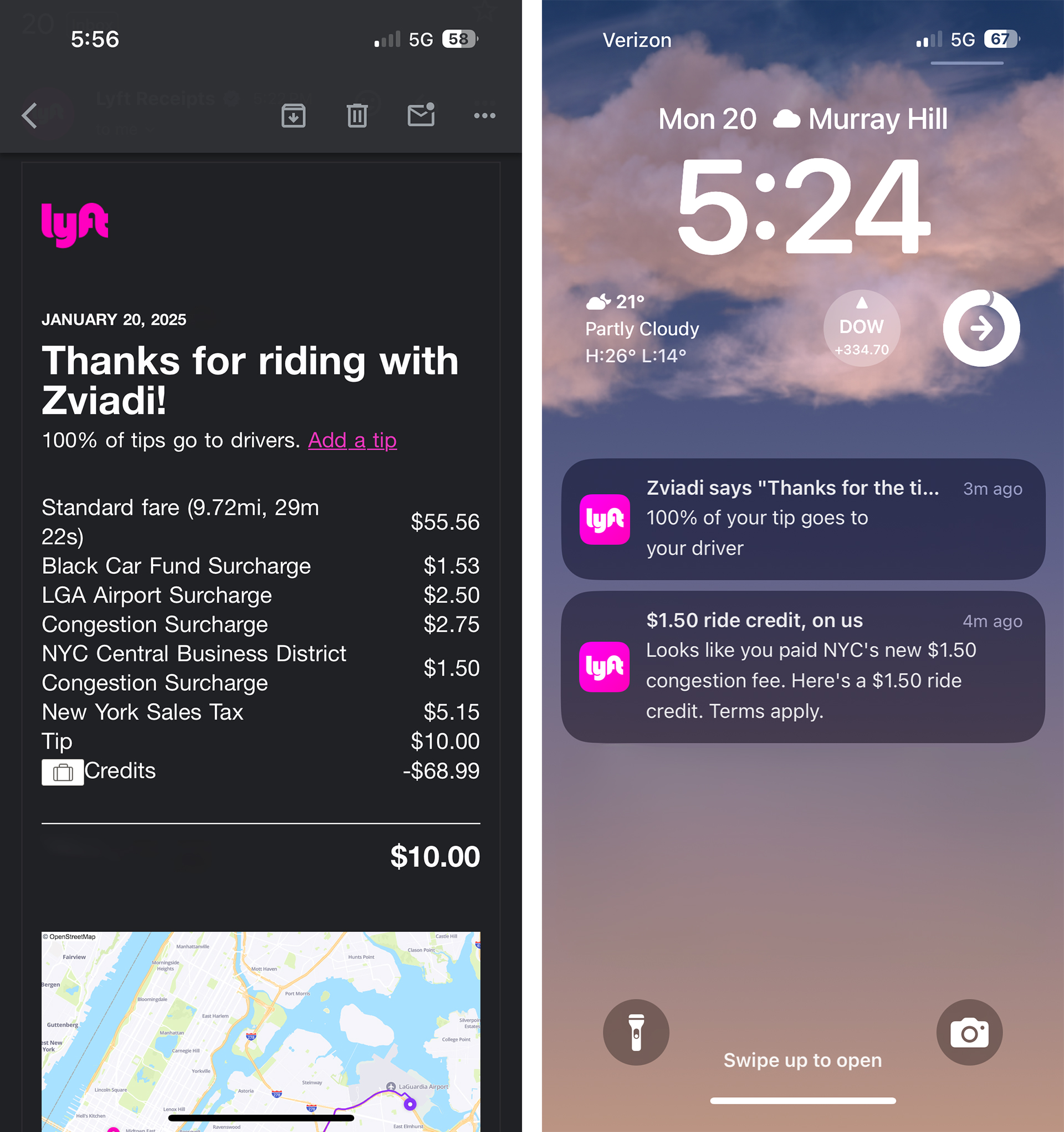

I used Lyft to enter the congestion zone and was charged an extra $1.50 per ride. Interestingly, Lyft voluntarily credited the cost of the congestion zone toll to my account each time to be used in the future.

Only today, I received an e-mail message from Lyft with the following request:

Brian, rides in NYC are some of the most expensive in the country. Now City Hall has proposed new regulations that will increase costs again.

This means more fare hikes, on top of the new congestion fee that went into effect on January 5. We can protect driver pay without excessive cost hikes.

Tell City Hall and the Taxi and Limousine Commission to stop making rideshare needlessly expensive.

I find the pricing of ride sharing services to be usurious in general in recent years and try to avoid them whenever possible. I should have done so this time around as well. For example, did you know that Lyft adds a congestion surcharge of $2.75 in addition to the “NYC Central Business District Congestion Surcharge” of $1.50?

Final Boarding Call

Perhaps I am biased; but I believe to this day that no other city is quite like New York for so many reasons…

…and perhaps that is part of the allure: people will still be willing to drive in and pay the congestion pricing fee if that is the best transportation method to use to enter the lower half of Manhattan.

Think about it: if the congestion problem is not resolved, New York gets millions of dollars in increased revenue just from the implementation of the toll for the congestion zone; and if the congestion problem is significantly alleviated, New York still gets less increased revenue but has achieved its purpose of relieving congestion in the lower half of Manhattan. Regardless, the toll for entering the congestion zone is still expected to increase from nine dollars to $15.00 in as soon as one year.

I am not sure how much was spent to installing 1,400 cameras at greater than 110 detection points throughout the city to monitor traffic entering the congestion relief zone — as well as traffic signs and other ancillary equipment — but I would estimate that cost to be $500 million, which the city should recover within a year.

Just because New York wins does not necessarily mean that its residents and visitors win. Whether residents ultimately benefit is still not definitely determined: anyone who delivers goods into the central business district of Manhattan and has no choice but to pay the congestion zone toll will most certainly pass on the cost to customers. Perhaps to some residents, that is worth the price to pay for less congested streets and less noise.

I can also only imagine some businesses — such as parking garages — suffering as a result. Some motorists will park their cars outside of the congestion zone — which means less revenue for parking garages — but after drivers pay as much as $31.81 in tolls just to enter the city from New Jersey, are they really going to want to pay as much as $55.00 per day to park a car?

As successful as the congestion zone plan will likely be for the city of New York, I personally still do not like the idea of having to pay an extra nine dollars just to enter a place which for years I have never had to pay extra before.

Now that Singapore, Stockholm, London, and New York have successfully implemented congestion zone pricing, will this scheme spread to other cities around the world? Do you believe that congestion zone pricing is the wave of the future for cities — especially if they are seeking ways to increase revenues?

All photographs ©2025 by Brian Cohen.